The thought processes and emotional lives of our canine companions is a huge area of research these days, and a question that keeps popping up and for which there’s currently no answer is, “Do dogs hold grudges?” As Marc Bekoff, Ph.D., professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado Boulder writes in Psychology Today:“Dogs surely don’t love everybody — human, dog, or other animal — and it’s essential to recognize this because this myth can harm dogs as well as the relationships they form with other dogs and their human companions. While some dogs might forgive and forget, others do not, because they remember what others have done to them or perhaps haven’t done for them in the past.”

While we don’t yet know (and perhaps may never definitively know) if dogs hold grudges in the same way people do, research does indicate there are measurable differences in the behavior of dogs who’ve been mistreated versus those who haven’t.

Does the behavior of formerly abused dogs offer a clue?

In 2015, researchers affiliated with Best Friends Animal Society published a study in the Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science that looked at the behaviors and psychology of dogs who’ve been abused, concluding that there are distinct differences between those dogs and “normal” dogs.

- Abuse of a dog can be active in the form of physical attacks or punishment. It can also be passive, for example, neglect. Abuse wears many different faces, including:

- Depriving a young dog of its mother through too-early weaning; Chaining or tying up a dog; forcing him to spend most of his time in a kennel or cage; making him live outside, away from his human family; Yelling, hitting or other forms of verbal or physical punishment; causing chronic stress or pain.

- Lack of proper care in feeding, grooming and attending to health needs; Partial or complete social isolation; lack of appropriate learning experiences

Depending on how old a dog is when the abuse occurs, it can affect him for the rest of his life, even if he escapes his abuser and is adopted into a loving home.

The research team identified abused dogs for the study using a multi-step process. First, they notified Best Friends magazine recipients that they were looking for owners of dogs who suspected their pet had been abused. They received over 1,100 responses, and each respondent was given a link to an online survey to complete.

Of the completed surveys, 149 were chosen based on the researchers’ assessment that the dogs involved were more likely than not to have been abused. The next step was to give five experts the histories and physical reports of injuries of the 149 dogs. After evaluating each dog, if four of the five experts concluded the dog had probably been abused, the animal was included in the study. This final step narrowed the field to 69 dogs.

The guardians of the 69 dogs then had to complete a highly detailed survey called the Canine Behavioral Assessment and Research Questionnaire (C-BARQ). The questionnaire is designed to measure a number of different canine behavioral characteristics and is considered by many to be the gold standard research tool for the study of dog behavior.

The 69 study dogs were compared with over 5,000 dogs in the C-BARQ database that were similar in age, the age they were acquired by their current owners and their living situation at the time they were acquired.

Abused dogs tend to perform 8 specific undesirable behaviors.

The researchers observed that the study dogs displayed higher levels of 12 behavioral characteristics, eight of which are known to be among the most common reasons people relinquish their dogs to animal shelters.

These eight traits and behaviors include:

Excitability; Fear and aggression toward strange people and dogs; Hyperactivity; Fearful on stairs; Attachment, attention-seeking; Rolling in feces; Persistent barking ; Bizarre, strange or repetitive behaviors such as hoarding, digging deep holes, compulsive sucking on pillows and circling.

In the case of abused dogs, their behavior doesn’t seem to indicate they hold grudges; rather, they develop maladaptive traits and behaviors, perhaps as coping mechanisms, which they bring with them after they’ve been rescued from their abusers.

So, dogs may or may not hold grudges, but do they feel shame?

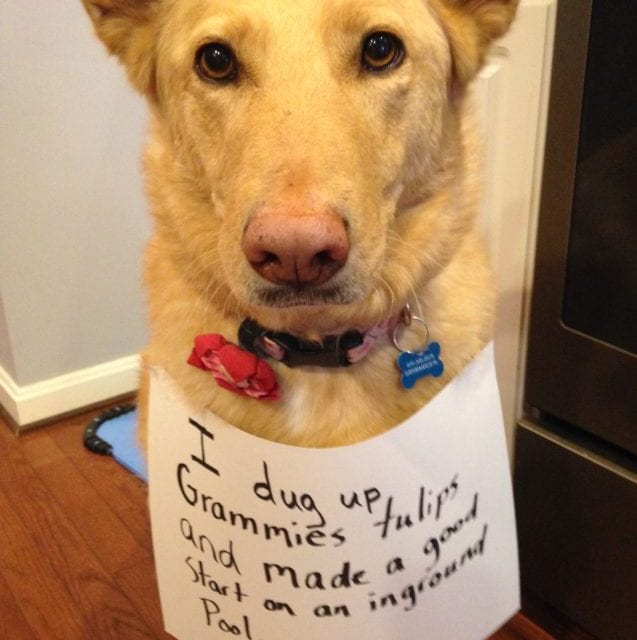

I’m sure most of you have seen some of the “dog shaming” videos and pictures that have popped up online in recent years. In many of them, the dog looks truly guilty or embarrassed, and the “thought bubbles” or signs the owners add to explain why the dog is feeling ashamed are often hilarious. But do dogs really feel shame?

Probably not according to dog behaviorists, who believe that hangdog look, you know the one — lowered head, ears back, pleading eyes — is simply your pet’s reaction to the hissy fit you’re throwing over something he did earlier.

In 2009, Alexandra Horowitz, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychology at Barnard College and author of the book, “Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know,” published one of the first scientific studies on dogs and feelings of guilt or shame.

Horowitz’s study involved 14 dogs who were put through a series of trials to see how they reacted when their owner told them not to eat a treat, and then left the room. When the owners returned, sometimes they knew what the dogs had done, and sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes the dogs had eaten the treats, and sometimes they hadn’t.

Horowitz observed that the dogs assumed “the look” most often when their owners reprimanded them, regardless of whether or not they had disobeyed. And in fact, the dogs reacted more to a scolding when they had behaved themselves than when they were disobedient.

According to Horowitz, the dogs weren’t displaying “guilt,” but a reaction to the owner’s tone of voice. However, she doesn’t rule out the possibility that dogs may feel guilt — she simply points out that “the look” isn’t an indication of it.

Of course, our dogs certainly do learn from their bad behavior, but only if our reaction occurs as the behavior is happening, or immediately afterward. The longer the elapsed time between your dog’s bad deed and your reaction, the less connection she’ll make between the two.

Of note, I spend allot of time reading and researching everything I can to better understand a Dog’s Perspective so when I am asked questions at the Kennel I have something to contribute. In the short time my wife and I have owned this new venture of ours I am learning that the relationship between our Dogs and ourselves is very complex.

Working with a Dog like I have in the military and in law enforcement you do have certain insights but thanks to our clients at the Kennel I am clear I still have allot to learn, especially if I want to be helpful to our clients both the two legged and four legged ones.